Addressing Climate Change and Economic Development at the Same Time

The world's citizens face a seemingly contradictory challenge: how to lighten our heavy carbon footprint while at the same time lifting the economies of the world's developing nations.

By Roger Strukhoff

The first part of the challenge seems existential. If we don't make serious inroads to eliminate CO2 and related emissions from our atmosphere, we face the prospect of an uninhabitable planet sooner rather than later. Yet two-thirds of the world's nations have a per-person income below the world median (of about US$10,000), and a higher imperative exists in most of them: raise the living standards of their people.

What We Can Measure, We Can Address

To address this situation, a small group of colleagues and I have developed a group of indices and rankings over the past decade that measure the relative technological progress of nations, and the relative difficulty they face in addressing climate change and economic development at the same time. By applying this data, national leaders and their people can design their own specific paths to improving their socioeconomic situations while doing their part to address anthropomorphic climate change.

We place technological progress at the center of our research because we believe there is a correlation and causation between what we call digital infrastructure and positive socioeconomic development. More and faster connections to sea cables, more and faster local internet connections, more mobility, more data servers and data centers, and the jobs that go with them are a positive thing, we believe. We balance that with a suite of socioeconomic factors that often impede progress, such as income disparity, the perception of corruption, the state of roads and bridges, and the relative cost of living.

Taking a Relative View

What makes our work unique is our relative approach, that is, we look at relative rather than absolute progress within the 143 nations for which we have data.

We start with publicly available information from well-known sources such as the United Nations, World Bank, International Telecommunications Union, Transparency International, and others. We then use a series of integrations and derivatives in pursuit of answering this question: “how well is each nation doing, given its current socioeconomic situation and resources?”

This creates what we believe to be a uniquely fair-minded view of these nations. This approach differs dramatically from traditional country analyses, which weigh any number of factors to create a straightline, predictable result.

Not Just a Measure of Wealth

I was inspired to start this research when I lived in the Philippines a decade ago. I was struck not only by the vast disparities in wealth there, but also the sheer dynamism in certain pockets as an exuberant, resilient group of people fought daily to achieve somewhat of a middle-class existence. How can I measure this dynamism? How can I show that developing nations are not simple, impoverished charity cases, as it seems many people assume?

The traditional approach predictably informs us that Switzerland is a wealthier country than the Philippines, for example. But it is unable to discern how well each of those nations is progressing, given its current situation and resources. Rather, it delivers a simple mapping of wealthier countries on top, developing countries on the bottom.

Our approach, by looking at things relatively, can uncover diamonds in the rough as well as laggards that may surprise people. In our most recent core index, which we call the Tau Index, we find the nation of Georgia as the relatively most dynamic place in the world. Other nations in our Top 10 include Ukraine, Estonia, Moldova, Bulgaria, Rwanda, Denmark, Vietnam, the Netherlands, and Serbia.

We have also developed sibling indices that measure such things as immediate change, tech-only progress, and a “Goldilocks” group of nations that are neither developing too quickly nor too slowly.

It should not surprise anyone that the United States is merely in the middle of the pack, as its average internet speed, cost of living, and steadily increasing income inequity, to name three factors, are hardly world beaters given the vast wealth of the nation.

Updated to Measure the Challenge to Reduce Emissions

Now, over the past two years, my colleagues and I have been able to add new data about emissions and energy use to create new measures that are relevant to climate change. An index we call the Emissions Reduction Challenge (ERC) Index is part of this new work. This index examines the scope of emissions by each country and its inherent, socioeconomic ability to address their emissions. As one might expect, there is a lot of bad news in this data, particularly given that the world's four most massive polluters – China, the United States, India, and Russia – all score very poorly in our new measure.

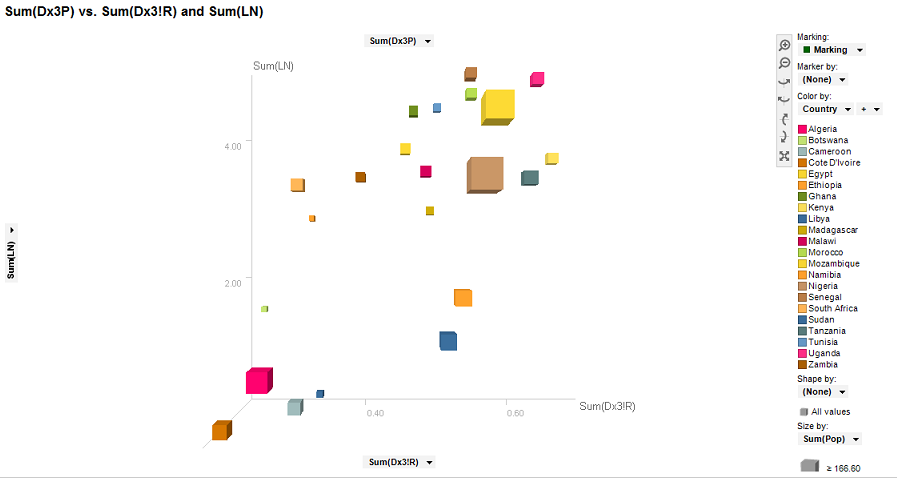

As we as a species grapple with this seemingly contradictory problem, it's worth noting that people in developing nations must get by on only 3% to 5% of the per-person electricity enjoyed by the developed world. Although it will be impossible in any reasonable timeframe to lift all of these nations to the developed-world level, we can ask how much it would cost to bring them up to a significantly more prosperous level, say 25% to 40% of the developed-world standard. (The graphic accompanying this article shows a projection of challenges in Africa, using our analysis. We are happy to discuss its details at any time.)

We can put a number on achieving this

The Tau Institute analysis on behalf of the Climate 4.0 Project of the Smart Nations Foundation shows that an investment of between US$700 billion and $1.5 trillion could do it. Done over 10 years, this represents, at maximum, less than 0.2% of the world's GDP each year.

Our other research puts a similar price tag on significantly reducing emissions. And our core research can be used to measure and price the overall challenge of socioeconomic development.

We clearly understand that none of this measurement or possible investments exist in a vacuum. The world continues to be a troubled place full of conflict and violence. There are serious challenges to create and maintain stable, fair-minded governments; to avoid and resolve local conflicts; and to participate in effective international agreements and initiatives.

But we've seen some small, iterative progress from sharing our data and supporting specific initiatives. We believe that our work can do much more. My colleagues and I refuse to give up hope that we can, indeed, maintain an inhabitable world in which we can all live more peaceably and prosperously.